Plastic Paddy

I was born into a warm, loving, Irish home. Faith, family and a strong work ethic were the backbone of my parents’ existence. The other people who helped raised me, taught me my history and enriched my developing years, were Big Tom, the Wolfe Tones, The Chieftains and The Dubliners who filled the house with music and enlightenment. I thank you all sincerely for the education.

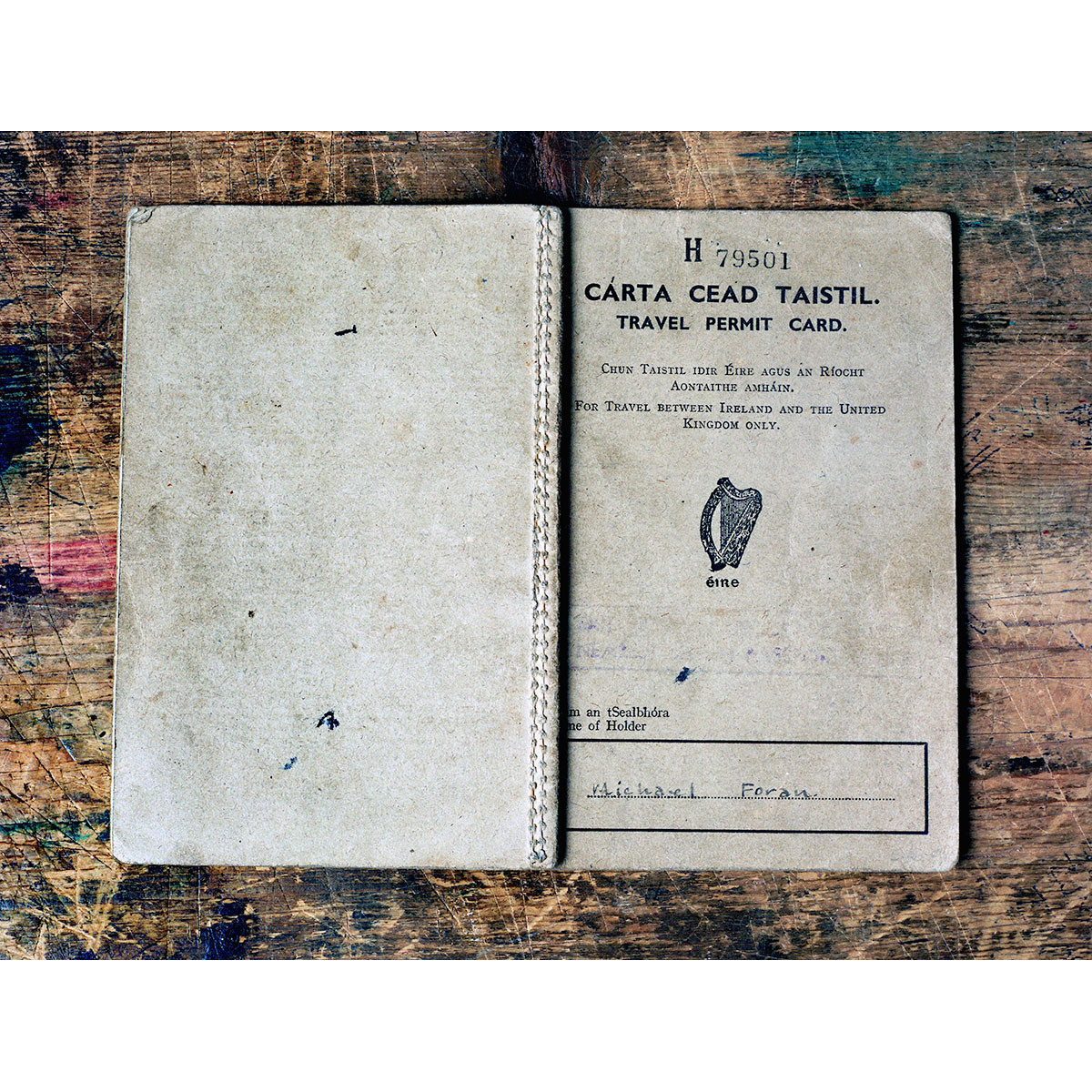

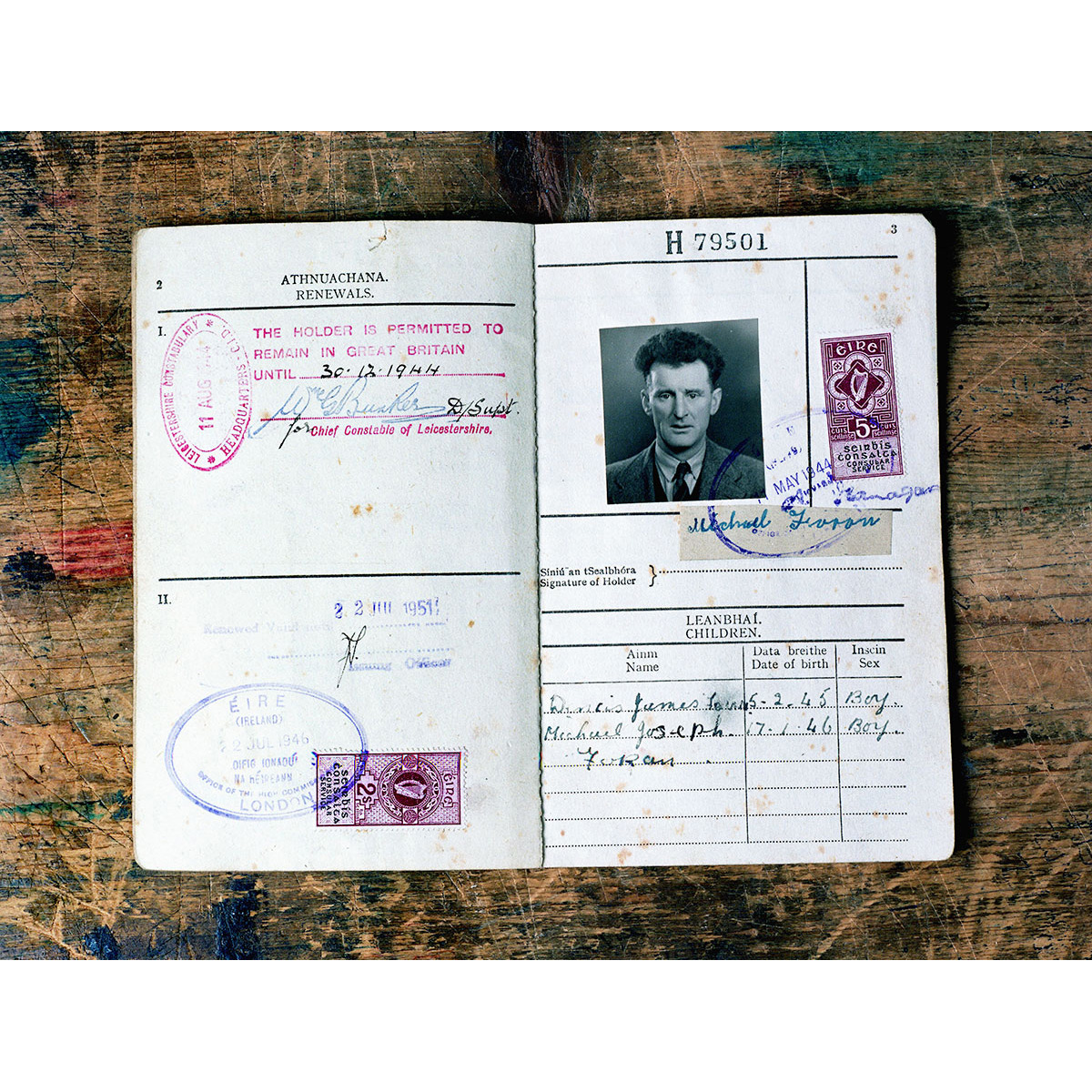

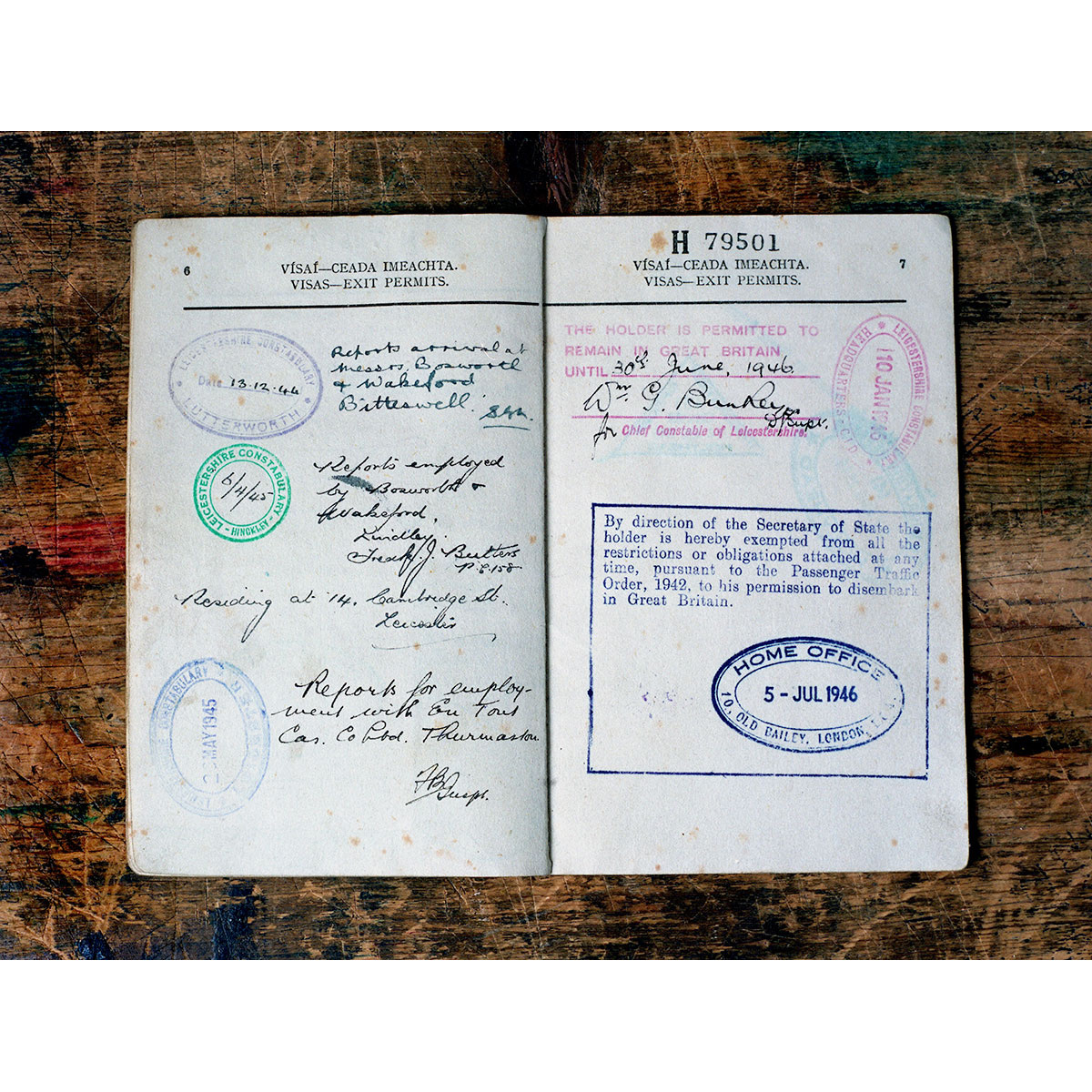

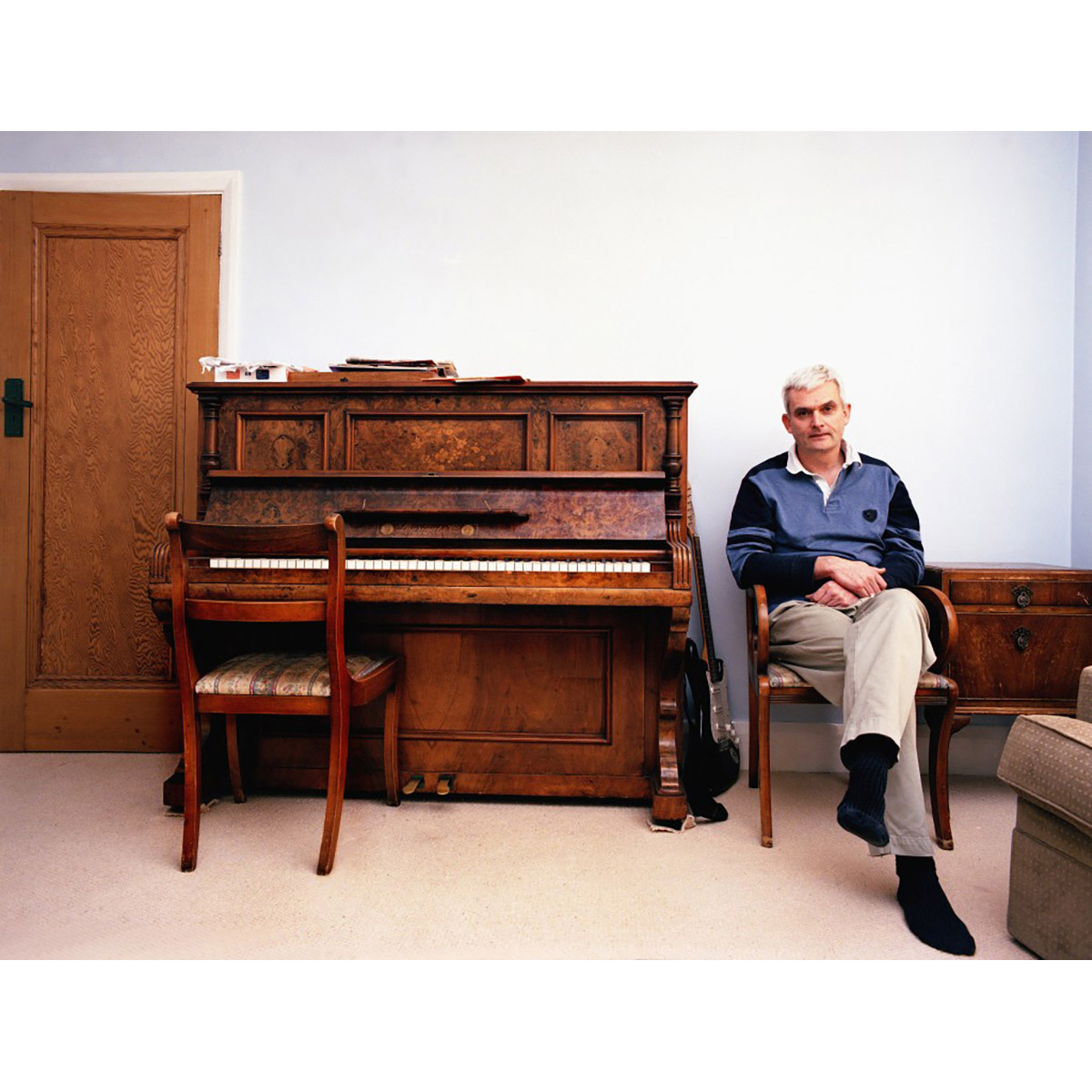

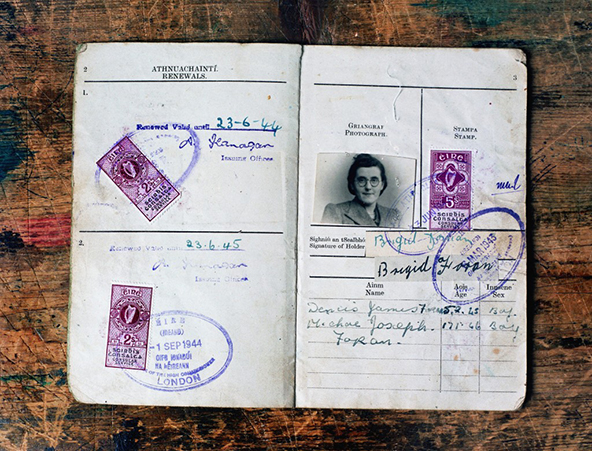

My father was born in Cork and my mother in Roscommon. They met, married and raised a family in England (Leicester). From the day I was born I was an Irish citizen via my parents’ passport. Through going to Catholic schools, the majority of my mates had Irish parents who had, likewise, come over to England for work, and settled. Most of us made regular trips ‘home’, looked Irish, sang Irish songs, played Gaelic football and embraced all aspects of Irish culture. We were, however, born and raised in England, so were we Irish or English? When we hit our teens we had the choice to be Irish or British citizens through our passport choice. I declined the opportunity to become a British citizen not through some form of misguided schoolboy politics but simply because there was no choice in my eyes. Weeks later my green passport arrived.

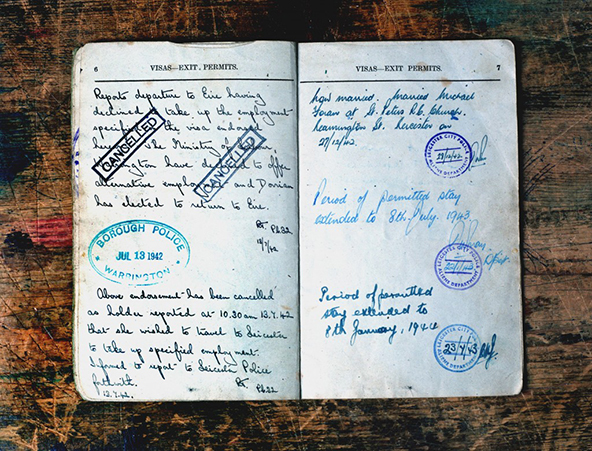

It’s worth remembering that this was 1980’s Britain, a country whose citizens were being bombed and killed by the IRA. For our parents (not for the first time) their accents could, and were being held against them. This was a time when ‘choosing’ to be Irish was not popular, but you either hid away or wore your brightest colours. Denouncing the bombings and trying to explain that these tactics did not represent the views of the community seemed to do little to convince the suspicious. Over time, being Irish has no doubt worked for and against its citizens living in Britain, as one of my interviewees (Josephine Feeney) said:

In 1974 when the pubs in Birmingham were bombed there was a very, very strong anti-Irish feeling especially in the Midlands. The police investigation did ripple as far as Leicester. I’m glad to say that attitudes have changed a lot. Immigrant groups always go through this kind of situation where they’re despised, rejected, tolerated and then rejoiced.

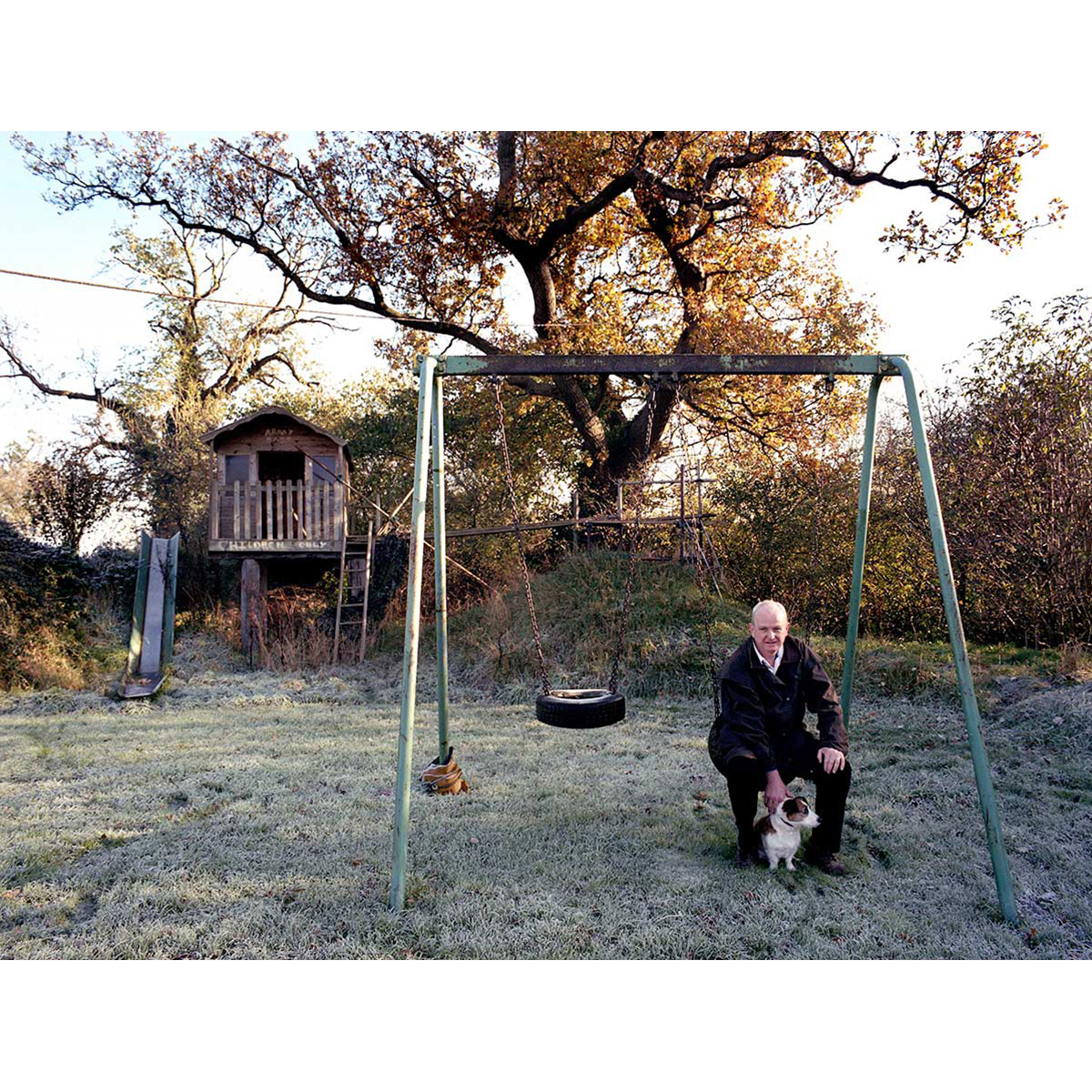

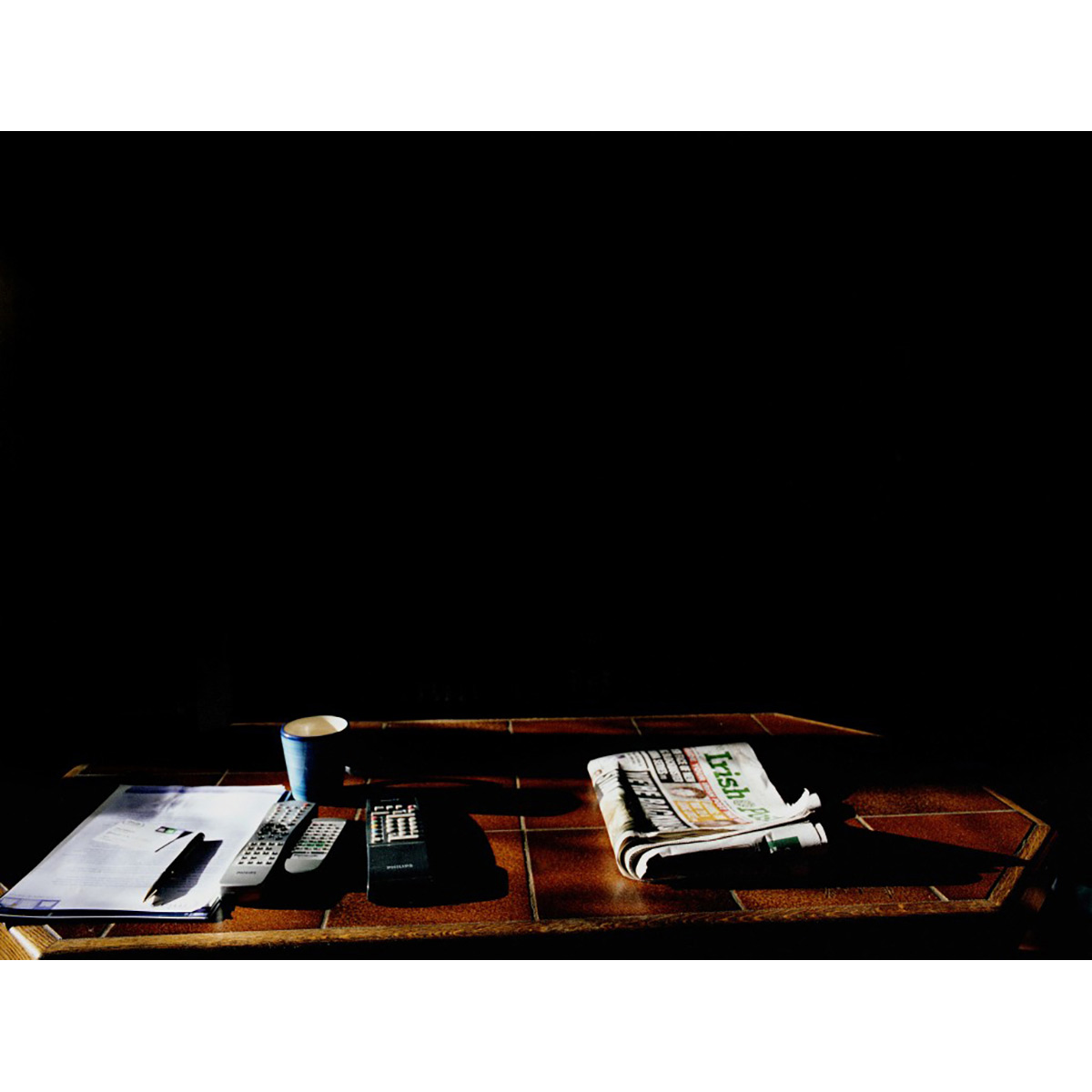

So where did we fit in this turbulent cultural melting pot? Flying to Ireland in the days before budget airlines was an expensive experience, and if you had to get the ferry across the sea it was also a long, long bumpy crossing. However, this was something you needed and wanted to do. As a child, the thought of spending three weeks in West Cork on the family farm with a beach three minutes away was hardly a chore. Bringing in the hay, going for adventures by the river and playing ‘hurley’ with your cousins brings back warm memories. This was far more than a holiday! The worst part was always the day of departure. I remember my father having tears in his eyes. Were the tears for his relations, some of whom were getting older and whom he might never see again or were they for the home he was leaving once more? I never asked. Nobody likes to see their parents distressed and if truth were told tears were flowing down the cheeks of the two boys in the back of the car (my brother and I) also. I believed that those feelings of sadness on leaving Ireland were my father’s and that my brother and I were simply reacting to his sorrow, but adult life has taught me differently. The gut-wrenching feeling on departing Ireland hasn’t dissipated. I will find every excuse to visit Ireland, to visit ‘home’. After marrying a girl who’s father is from Derry I discovered that not everyone (of Irish parentage) shared my sense of Irish Origin. She considers herself firstly a Londoner and then a European.I have met people born of Irish parents through this project that believe that your place of birth and residency makes you who you are. On the other side, I’ve met people like myself who don’t believe they ever chose to be Irish, but were born Irish.

Eamon de Velera promised his people work and good standards of living in Ireland, yet until the decade leading up to 1990, 50,000 people per year emigrated. We are a result of this. Place of birth does not represent people’s origin, that is determined by a list of variables, which at birth, are out of our control, primarily politics and economics. We could argue for our national identity until our last gasp of breath, but why bother. Few things in life are simple why should your nationality be any different?

The Irish Constitution was amended by referendum in 1998 to acknowledge the importants to Irish history of the diaspora, and its relationship to Irish citizenship. This may seem very overdue considering that there are five million people in Ireland, but approximately 70 million people worldwide, entitled to call themselves Irish.

Ádh mór ort!